Born and Bred in Myanmar: A Book of Five Short Stories is a window into the daily lives of five main characters, brought to life by the Burmese author Moe Moe Inya. The world they inhabit, though fictional, is a mirror image of Myanmar (Burma) in the 1980s, a reflection the country in the chokehold of the former strongman Ne Win’s socialist government, frozen in time and cut off from progress. Writing under the watchful eyes of the heavy-handed censor board, Moe Moe Inya could not throw the window wide open. She had to depict her characters’ hardship and hopelessness without pointing the finger at the true culprit: the government’s misguided policies and corrupt bureaucracy.

Reading these stories, you feel the protagonists’ suffocating circumstances, the cruel Groundhog Day they are doomed to repeat. But don’t expect these heroes and heroines to take up arms against the slings and arrows of life, to rail or rebel against the system. The repressive atmosphere in which these stories were written wouldn’t permit such grand gestures. You should keep in mind that they were by an author who could only show you the damage and the devastation but couldn’t talk about the elephant in the room.

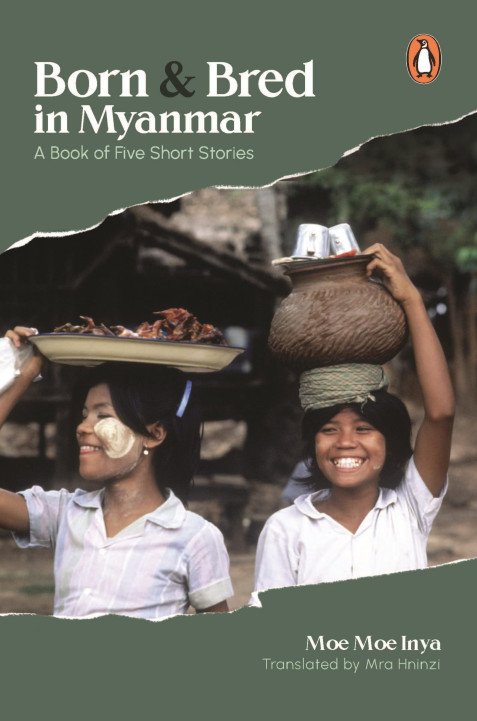

Moe Moe Inya, Born and Bred in Myanmar. A Book of Five Short Stories. Translated by Mra Hninzi. Singapore: Penguin Random House, 2022.

In the first story, we meet Khin Soe, a young boy eking out a living as a porter at Kyaiktiyo Pagoda, better known as the Golden Rock. The boy and his friends should be in school, but education is a long-term investment that their parents cannot afford. Their empty stomachs demand a more immediate fix. As a result, the boys learn to pull their own weight, quite literally, by carrying pilgrims’ luggage up and down the mountain.

The father kept saying repeatedly that he would send the boy back to school when he had recovered and could work again. But Khin Soe did not consider it a burden to shoulder the responsibility. There were many other youths of the same age at Kin Pun Sakhan who happily went up and down the mountain with heavy loads. The loads on their backs transformed into cash money, which provided them with subsistence amount for their daily life.

Accompanying Khin Soe and his clients, we begin to see Kyaiktiyo’s tangled web of economy, sustained by the porters, souvenir shop owners, and food vendors who compete but also cooperate with one another.

“How many persons are there?” the rice shop owner, Daw Yi, asked.

“It’s a group of twelve, Aunty. They are well-to-do people. They are sure to buy food from you.”

Daw Yi had the habit of asking if the customers were wealthy and that was why Khin Soe told her before he was asked.

Moe Moe Inya’s characters routinely address their own family members as well as complete strangers with kinship terms, such as sister, uncle, or aunty. The young porter Khin Soe addresses his own mother as “mother,” but also calls the restaurant owner Daw Yi “aunty.” It’s a reflection of the local custom, of the way Burmese people speak. For some readers unfamiliar with this practice, however, the jumble of kinship terms may prove quite distracting.

In the second story, we meet Moe Kyaw, a long-distance bus driver doing his best—and failing—to earn a few precious words of praise from his father.

Along the bumpy road between Kyaukpadaung and Popa, Moe Kyaw had to drive his dilapidated little car with a full load of passengers three times a day. Though [his] father could now stay at home in leisure, he did not see Moe Kyaw as his comrade. In his mind, the boy was just someone who drove the car because he did not want to study.

When Moe Kyaw gets a private moment with Hla Lay Sein, the daughter of a food stall vendor, she plays coy, feigning jealousy.

“Of course, I’m a foolish girl. As for the girl passenger in your car, she is pretty like a porcelain doll and you could not even eat but gaze at her as if your eyes would fall out. This girl saw everything from the kitchen.” “Stop it. Do not talk rubbish. I’m unhappy because the old man at home said harsh words to me.”

The stiff dialog suggests the playful banter from the original is lost in the literal translation. A light touch by a skillful editor might have eliminated these rough spots in the stories.

In the fourth story, you meet a village doctor who wants to give the gift to education to Ma Nyo Pyar, the daughter of his old flame. But the girl’s parents need her labor to make ends meet. Explaining why the girl must drop out of school, the mother says, “It’s not that I do not want to have her educated because she is a girl, Ko Aung Khaing, but she is indispensable. Last year, our vegetable produce could not be sold because she was not here. Next month, the chili seedlings have to be sown.”

Moe Moe Inya’s dialog-driven storytelling immerses you in the sights and sounds of rural Myanmar. It puts you in the middle of the human dramas playing out in the bottom layer of the social stratosphere. Her stories are also about the sacrifices and concessions ordinary people are asked to make, about deferred dreams and fading hopes. In these stories, when there’s a tug-of-war between a promising future and a practical need in the present, the latter usually wins.

In the transition period between 2011 to 2021, Myanmar slowly began catching up as it took faltered steps toward democracy and civilian rule. In this sunny decade, young people like Khin Soe, Moe Kyaw, and Ma Nyo Pyar learned to code, worked for civil society organizations funded by foreign donors, and traveled abroad for human rights workshops. But sadly, with the military coup of February 2021, the country is regressing back to its bleak past. The everyday martyrdoms depicted in Moe Moe Inya’s stories are once more becoming a reality.

Kenneth Wong is a Burmese-American author and translator, born and raised in Yangon, Myanmar (Rangoon, Burma). He immigrated to the U.S. with his family in 1989. His essays, articles, short stories, and poetry translations have appeared in The San Francisco Chronicle, Myanmar Times, Irrawaddy, and Boston University’s AGNI magazine, and Center for the Art of Translation's Two Lines Journal, among others. He teaches Beginning and Intermediate Burmese at the University of California, Berkeley.