by Annie Malcolm

“Go to Wutong Shan, I hear that's where the real artists live.”

"Wutong Shan is a looney bin."

"Wutong Shan is utopia"

"I'm moving to Wutong Shan."

"Why? Have you fallen ill?"

"Everyone in Wutong Shan is a master."

"Everyone in Wutong Shan is crazy."

"Wutong Shan is special... the best place in Shenzhen."

"Wutong Shan is not like the rest of Shenzhen and Shenzhen is not like the rest of China."

"Dafen is business. Wutong Shan is art."

"Wutong Shan is not normal life. This is not real."

On the outskirts of Shenzhen, China, at the foothills of Wutong Mountain, is Wutong Art Village. Wutong is a space constituted by a history of large-scale production in factories, a contemporary economy based on art and spirituality, and uncertainfutures. Because of its reservoir, which is Hong Kong’s water source, Wutong is not developing in the raze-and-build fashion of many of China’s urban fringe areas. Rather, inhabitants change the built environment by converting factories and original village houses into art studios, live/work spaces and shops.

The Method

It is not unusual for an ethnographic account to open with a story about the ethnographer traveling to the field, and anthropologists with different theoretical orientations may employ a similar writing strategy of this kind. In so doing, the anthropologist as an author creates, among other things, an ethnographic authority that rests on the fundamental assumption, implicit or explicit in writing, that these experiences are out therein reality. (Liu 2002, 19)

-UC Berkeley Professor of Anthropology Liu Xin

Living in Keng Bei Cun, one of the eight villages of Wutong, I produced a document, together with seventy-five informants. I asked non-artist informants about the revival of traditional Chinese cultural forms. With artists I participated in land art interventions, translated gallery wall text and the only book about Wutong Shan, Wutong Smoke Mist and Clouds, by the Scenic Area Management Department (the government), collaboratively with villagers, into English (陈俊开 2010). I accompanied artists on trips to other villages to buy materials.

As Jeanne Favret-Saada writes, “My notes were obsessively precise, so that I was able later to re-hallucinate the events, and because I was then no longer ‘caught’ in them but became ‘caught’ in them again, I did eventually understand” (Favret-Saada 1990, 192).

*

Professor Liu, based in China, is the man behind the book Wutong Smoke Mist and Clouds. An excerpt of the prologue reads,

The city has history, the mountain has stories. Wutong Shan silently stands here, gazing at the life of this place’s people, remembering even the great changes of the past. Opening this book Wutong Smoke, Mist, and Cloudsproduces a “long time no see” feeling of warmth about Wutong Shan and the local historical data and legends that vividly unfold one by one before us. Much of the historical data has never been seen before, this is valuable material that cannot be found in a history book.

Liu is a botanist in the Scenic Area Management Department who wanted to understand Wutong Shan, collect data and do research, so he wrote the text. I met with him and we hiked into the mountain where he checked on his plants and flowers. The village sits in the foothills of the mountain, and walking up its main street takes you right to the gate of the national park, the bottom of the mountain. After walking through the gate (which is guarded by a man in a booth) you’re on a paved path that goes up the mountain, to “Big Wutong” and “Small Wutong,” the two peaks (Big Wutong is about a three-hour walk up). As you ascend, there are views of the villages below--blue roofs indicate factory buildings, original village houses crouch below, little roads careen in between, and bridges lay over the streams that trickle down from the mountain. Assigned the job by the government, Liu has been working in the Department since 1996. I asked Why more art villages? and he said it’s because life is getting better, so more arts and culture is required.

“The Cultural Revolution and that time of darkness didn't have open doors so now we have we do this.”

(Later that night at the enzyme shop CALLED (which sells tea, handmade cotton clothes, essential oils, goji berries and other health and healthy lifestyle accoutrement), I met a person who calls himself a culture teacher. “During the Cultural Revolution our culture was destroyed,” he said. “Now we are picking it back up. Because of Hong Fasi, the temple nearby, this is a place where many people gather to revive traditional Chinese cultural forms.”)

In recent years, Professor Liu remarked, more artists have come to live here, giving the place an yishu fenwei (艺术氛围 - an artistic atmosphere). “The creative industry is still backwards, it doesn't have a kind of fanrong ganjue (繁荣感觉-feeling of prosperity).” Liu aims to make Shenzhen more beautiful through art and flowers. Liu said the more beautiful a city is, the higher the intellect of its residents, and the more global it is.

What’s the relationship between art and flowers?

Liu explains that flowers, like art, do affective work, they make people happy, because they are vehicles of beauty. Also, he says, they represent a raised quality of life. After you’ve fed yourself, these are the kinds of things you want - art, flowers.

*

King tells me he’s a professor of Marxist thought.

LL says, There’s a responsibility to spread guqin (古琴-a traditional Chinese instrument -culture, so I came. Whether the government had asked me to come or not, I would have come.

Me: And they...

K: They support me.

Me: Did they have this dream, to make this museum to support traditional Chinese arts?

K: Yes, right, qinqi shuhua (琴棋书画 - instruments, board games, books and paintings –ancient Chinese arts hobbies – it’s the basic things ancient Chinese did.

(修养-xiuyang — to recover, also that which brings you into the upper class –that which acculturates).

*

China has many art villages, in and around its big cities. In Shenzhen, the art village narrative is one of government intervention, not to stop the art village but to make various moves to lay claim to its success. Shenzhen is complicated by the fact of the urban village form; Jonathan Bach writes, “Together with the city we ask, pragmatically, ‘What needs to happen to make the villages disappear?’ but we suspect, thirty years since Shenzhen’s inception, that the real hermeneutic question is why the villages persist” (Bach 2017, 142).

As seen in the cases of other urban villages, negotiation between the Shenzhen municipal government and urban village administrations is a long and complicated process whose results are unpredictable (Bach 2017; O’Donnell 2017). City planners and architects are now in talks about how the government can “act as a wall” between the market and the artists in Wutong Shan so that increased housing prices will not affect whether or not artists can afford to live there, thus preserving the artistic atmosphere that gives the place value to begin with. This conversation is embryonic and informal; the city planners gather at the design center on the weekends and have no clear plan yet as to how to convince the government of the value of this place. Ethnographic research at this phase of the development of the village afforded insight into the conditions of possibility for the current state of affairs as they are made evident by everyday life, and the imagination of the future of Wutong.

I learn about the city plans in two places: the Shenzhen Design Center, and at a guest house named April Street (四月街), whose owner has a master’s in city planning.

“The government originally planned to unify and purchase the original village people’s houses, renovate them and then rent them out to artists at a subsidized rate,” the owner of the guest house told me. “The government renovated some houses and made some infrastructural improvements to the area but without purchasing the houses. After the environment improved, the village people raised the rent to double or more. Because the government couldn’t accept these prices, their program failed and they abandoned it.” The government, after all, had no way to control prices.

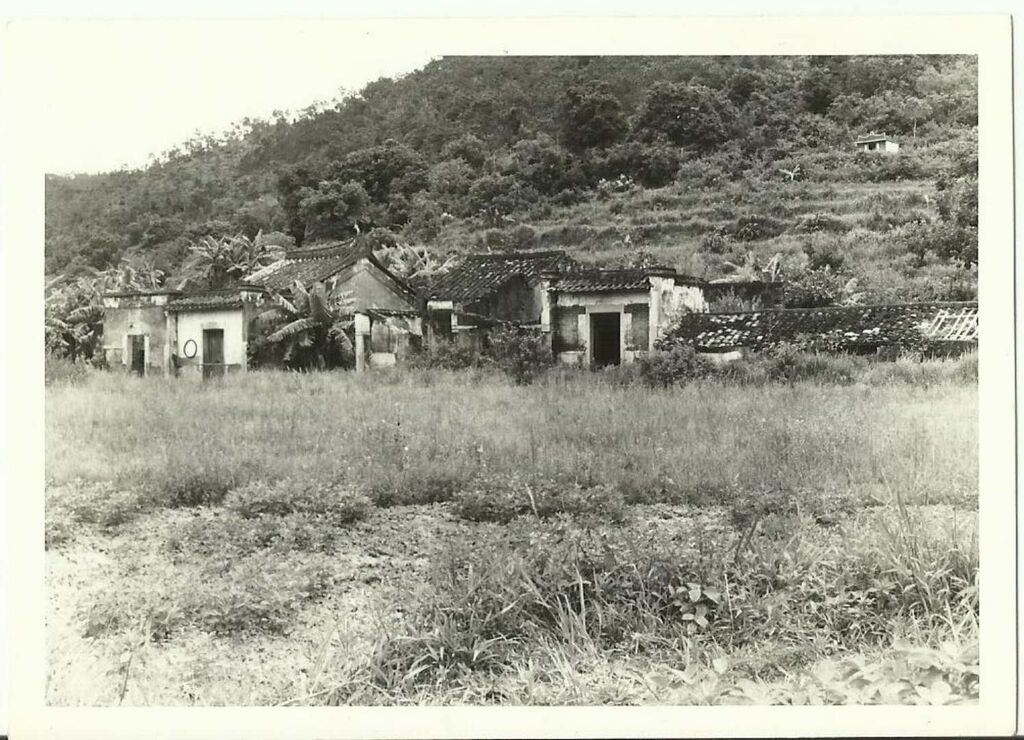

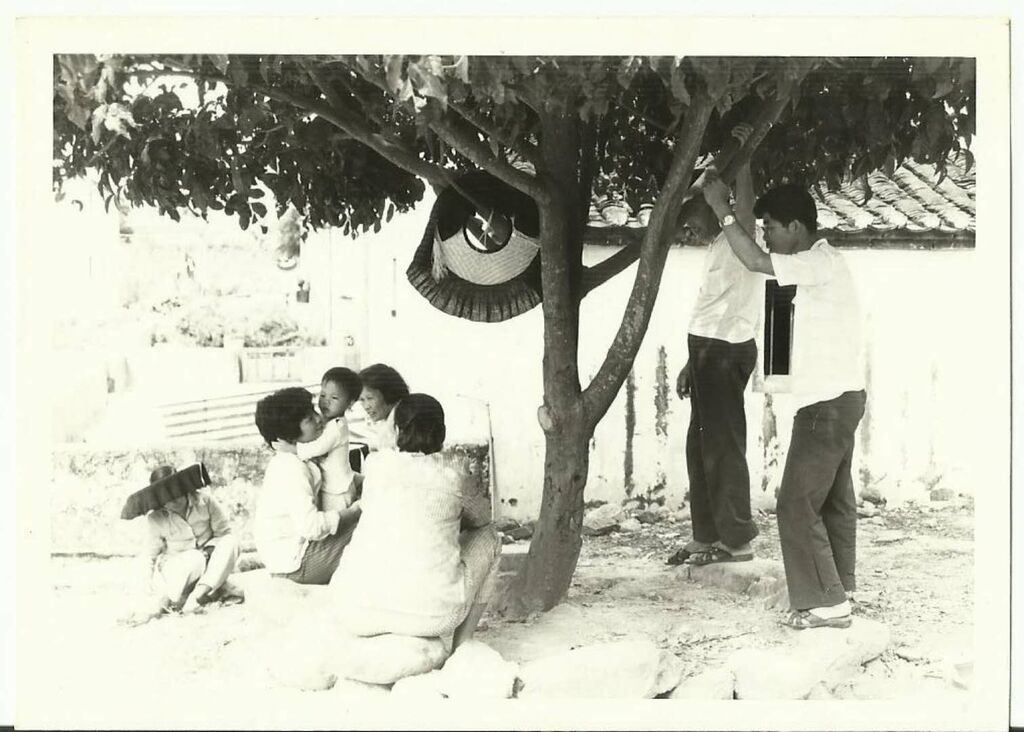

Twenty years ago the land where April Street now stands was all farm land. With no other form of transport, the landlord rode a bicycle to Dongguan to hire a fengshui shi (风水师 - fengshui expert) to consult on the building. That’s why there’s space around the building. When she signed the lease, the landlord showed her photos of the land before he built on it, thirty years ago. She’s guessing the timeline based on the age the children -in the photo he is 4-6 years old, now he is in his mid-thirties. Before us, she says, it was a xuetang, maybe, but when I came, it was already not a xuetang. (xuetangor guoxue xuetang - 国学学堂 - a national arts education school, or school where children learn the ancient canon rather than the modern curriculum).

We talk in the lobby, morning sun thinly spread, to the sounds of pop - “it’s now or never boy” - and twangy country music. We’re surrounded by bolts of colorful fabric she uses to make clothes and other small things, embroidered ornaments and purses, with the three sewing machines on the large table. She tells me she teaches classes on how to make these things in the space. Chickens tuck tuck nearby and the cold room smells of wood smoke and oatmeal cooking. Her mother in law is on breakfast in the kitchen.

*

An artist who is quiet - interviewing him is so hard - says, “Here... at the beginning it was like neidi (内地 - the interior) and nongcun (农村 -t he countryside) - and cheap.”

*

In the course of twenty-four hours the following two things happened:

A woman said to me, “Well if you want to study the rural, you should go somewhere else because this is the city.”

I asked a real estate agent if she had any houses in the area for rent. No, she said. “I don’t sell here, only farmers here.”

*

Work itself is differently configured in Wutong, as most residents do not work full time, but rather are ziyou (自由-freelance), pursuing a Do-It-Yourself, or DIY, lifestyle and a slow life. This takes place within the context of a recent move from made-in-to created-in-China (Lindtner and Li 2012), and in contrast to “Shenzhen Speed,” a phrase invented after the construction of the Guo Mao building in 1982 (the phrase of course masks the fact that labor was not suddenly performed faster; rather, more of it was performed in a shorter amount of time because of the scale-the number of workers and the number of hours they worked-the expression veils exploitation).

So if Shenzhen is the epicenter of DIY, Wutong is an iteration of that doing, in which the handmade is privileged over the quickly made. This is not to background the contemporary art practice taking place; artists in Wutong Shan have studios and make paintings, ceramics, sculptures and performance art. They are in a tight community with one another, thriving off the balance of peace and space, and proximity to both each other and the city. I heard singing every night throughout the ten months I lived in the village between 2015 and 2017.

*

I interview a financially successful Wutong artist

A: This studio used to be a factory, right?

L: Right.

A: Producing...?

L: Wujin (五金-the 5 metals), knives.

A: When did it stop production?

L: Five years, then no more industry...these kinds of factories are fewer and fewer... Ten years ago this place had tons of industry.

A: Speak slowly. The tea is good.

L: Wutong Shan, this place, the culture is very baorong (包容-forgiving, tolerant, to contain, to hold, inclusive). If you live in Shenzhen and you don’t live in Wutong Shan, and you live somewhere else, you won’t have this kind of feeling.

A: What kind of feeling?

L: You won’t feel this kind of cultural qixi (气息-breath, flavor). Because this place is very special, lots of things you can’t find in the city. You have here traditional Chinese culture, not the kind of culture you learn in school, but the ancient stuff. This kind of knowledge is very hard to understand. I also don’t understand it. But I like it. They had different (Chinese) characters back then. Several hundred years ago, this stuff. My kid learns modern education. But I believe in this kind of guoxue xuetang (国学学堂-national arts education school). A long time ago they only had Math and then this cultural stuff - the arts. But now you have to learn English, Physics, Chemistry,...

A: I think Wutong Shan... the story of this place and art are inseparable, so this part is very important.

L: Wutong Shanis an art village. If a stranger comes and tries to find artists, he’ll have a hard time, they wouldn’t know where they are because all the artists are in their houses. You need friends to introduce you. The artists here aren’t only painters, some are musicians, writers, poets, novelists,... including you.

*

People stroll in and out of live music venues and fine art galleries and visit each other for tea; they share furniture and clothes in WeChat groups and in designated meeting spots, building homes out of hand-me-downs. Strangers help each other, invite each other in to see a painting or a view of the river, and organize outdoor potlucks and parties, some funded by investors who want to make the place more artistic through activity. With helping, sharing and entertaining, of course comes gossip, criticism and skepticism; public and private merge on the narrow roads, in studios, and in conversation.

*

Lincoln invites me over to have fun with him and his friends. I show up to the courtyard and discover it is his dog’s birthday party. Everything is vegan. The coconut cake (“we made a mistake; it's not raw”) is delicious. There is fruit, flax seed crackers, gingerbread, and a head of cabbage from a farmers market in Guangzhou.

The noise of children counting in the background.

There’s a man who is a translator of movies and texts. He says there are three energy spots - head - wisdom, heart -emotions, stomach - actions. Lincoln’s wisdom and heart are weak, he says after holding his hands over his body. My head and stomach are slightly weak but I’m pretty well balanced and my heart is strong - this is my advantage, he says, and I should work to continue to develop it.

We listen to a chant from John’s phone-ommm sound-with images of the chakras. John begins to ommm along with it. People begin to fold their legs in and meditate.

The vegan proselytizer across from me has lived in Vancouver so her English is great.

Behind her is a window through which I can see into Lincoln’s living room, into which several of the guests have moved from outside. They stand before his paintings, eyes closed, meditating on them.

One woman there has been fasting for several days.

There are candles on the table that are painted the same as everything in the house, including the piano, the walls, the shower and the paintings - a rainbow palette.

脉轮 mailun - pulse wheel - chakra

*

Chen Heng Chao is a single mom and Wutong newcomer who moved from Dafen in 2015. She runs Kindred Spirits Art Gallery, one of a few galleries in the area. We chat one night over homemade wine in the gallery, which is currently exhibiting garments made using old designs and natural dyeing methods, as well as Chen’s own oil paintings of peaches. At Kindred Spirits, Chen holds parties to cultivate the art scene. She considers the gallery a space for social practice, where she can gather many women—which is unusual for the Chinese art world—around art, Chinese culture, and beauty.

Earlier that day, a wealthy Beijing art collector had visited her and commented on the mess and smell of trash in Wutong’s little streets. Chen felt embarrassed. She felt caught between wanting to modernize Wutong into the sparkling city the collector was expecting, and her contentedness to enjoy her pet project and freedom to explore in this old style village.

Ruffled, we walked down the street to have tea with Xu Gengliang, who has lived in Wutong since 2009, about improving theconditions. Xu’s studio is filled with unique ceramic pieces, Buddha figures set into frames like paintings, and handmade tea cups, which are scattered throughout the whimsical, well-lit space. The two talk about how they could get citizens to clean up rather than get the government to step in. Xu has been in Wutong long enough to know that if something needs to get done, a citizen-led effort was a surer bet than government support.

The conversation meanders to the topic of the art industry in the village, and eventually they conclude that Wutong artists should open their studio doors and keep consistent gallery hours in line with mainstream art institutes. Though Wutong can pride itself on its traditional Chinese practices, it’s ultimately still a villageon the outskirts of Shenzhen, and therefore will always be influenced by its wake:

Xu says later in the conversation,

At that time, we were making small talk... but actually I don’t put Wutong Shan at the center (of my work). The center is outside. Because, after all, Wutong Shan is clearly small. The few people surrounding me are my regular customers. When I was in the city and doing my exhibitions before, someone collected a lot of my artwork, and one day he wanted to come in and visit. He drove around my house twice and couldn’t find somewhere to park and never came back. We had to arrange to meet in the city. The group of people who can afford art rarely come to Wutong Shan. To them, one reason is it’s time-consuming and their time is limited because they’re rich. And if you talk about beauty, this place is a small, small scene of beauty; in Shenzhen, you have a lot of small scenes of beauty and big scenes of beauty. There are prettier places, like on the beach. If they really want to relax, they won’t come here, and there’s a lot of traffic, and it’s small. For those very rich people, there are better environments to talk. For those rich people, I choose a different environment in which to chat... there are a lot of places that suit their taste. They have a lot of options. We have a lot of qinghuai (情怀-feelings) for this place. We think it’s pretty good, because we understand WTS, right? We’ve been here a long time, we have a lot of emotions about it. Some beauty, you discover gradually.

*

In 2015, I met with Guangzhou contemporary artist Zhou Tao. In his film “After Reality,” we see what we imagine are agricultural workers weeding in what we imagine is a lush natural area. Zhou tells me that this is actually an area between zones of urban development;the land has been abandoned, the water is toxic and the “workers” are performance artists hired for the film. Zhou is questioning the temporality of urbanization; if imminent reality for these spaces is development, then what? What isAfter Reality? Studying art villages like Wutong Shan, I am interested in the same kinds of urban areas, art processes and historical questions as Zhou. He is an artist and I am an anthropologist. If contemporary anthropology has anthropologists experimenting, or “being artists,” and the social turn in contemporary art has artists “doing ethnography,” we are back at an old question: what makes an artist?

Zhou writes,

Sometime, when you observe the surroundings and people around you in detail, you will capture those hidden traces that connect with your inner heart. During these moments, you will forget the existence of the physicality of yourself or the subject; only feelings and ideas are flowing. This is precisely the starting point of a fiction. (Zhou Tao 2014)

Originally from New York, Annie Malcolm is an Anthropology Ph.D. candidate at the University of California, Berkeley, focusing on Chinese contemporary art worlds, urbanization, ideas of escape and utopia, and experimental ethnographic modes and forms.